Poughkeepsie

Polluters:

Brownfields Past and

Present

Brownfields are increasingly seen as a

potential asset for urban revitalization.

This paper is intended to be a first resource for anyone interested in

becoming involved in brownfield redevelopment in Poughkeepsie; we discuss

legislation affecting potential involvement, common contaminants and methods of

remediation, strategies for ensuring equity in redevelopment, and some

historical and geological information about conditions specific to Poughkeepsie

that are relevant for brownfield reclamation efforts.

Carolina

Lukac

Katie

Phillips

Siobhan

Watson

Introduction

Brownfields are increasingly seen as a potential asset for urban revitalization. This paper is intended to be a first resource for anyone interested in becoming involved in brownfield redevelopment in Poughkeepsie; we discuss legislation affecting potential involvement, common contaminants and methods of remediation, strategies for ensuring equity in redevelopment, and some historical and geological information about conditions specific to Poughkeepsie that are relevant for brownfield reclamation efforts. Across the United States, a variety of brownfield remediation projects have been started in the past two decades, motivated by the desire for more compact urban areas and the revitalization of city centers. As attention to brownfields has increased, legislation has rapidly evolved to encourage clean up and redevelopment. Site investigation and remediation technology have improved and community members have become more involved in the redevelopment process. With several changes to legislation, incentives, and technology, in addition to many interested parties, information about brownfields can be difficult to gather and dialogue between the participants can be easily stalled. We hope this paper will contribute to the development of an accessible source of information about local brownfield issues.

Poughkeepsie’s Brownfields

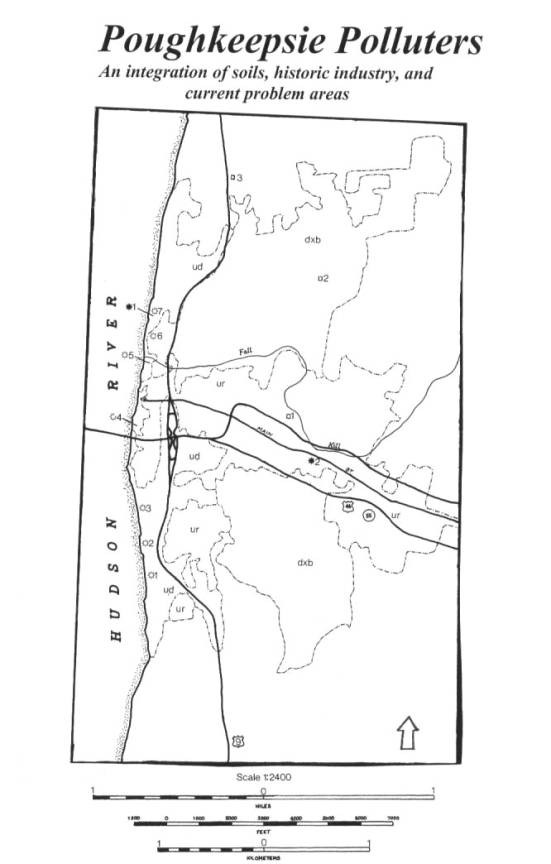

The difficulty in finding information about owners and development plans for possibly contaminated sites made our search for information on Poughkeepsie’s brownfields frustrating. The limited information we found about current brownfields demonstrates the need for a better resource base. Regardless, we now know that the Dutton Lumber site (located on the waterfront just north of Central Hudson) and the 400 block of Main Street are currently identified on the remediation process, as are three Superfund sites (Figure 1). Historical information about Poughkeepsie provided insight into places that may be considered brownfields in the future. We were able to identify past industrial use by studying historic Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps (1937), which show what industries have previously existed within the city of Poughkeepsie. The vast majority of industry was located directly on the waterfront (Figure 1). The main industries we identified were: lumber, metal, coal, oil refineries, and machinery and utility sites. Since coal, machinery manufacturing, and primary metal industry are all sites associated with chlorinated hydrocarbon pollution, the utility and industrial sites most likely caused some heavy metal contamination to the waterfront and the oil refineries probably left behind some petroleum hydrocarbons. Much of this noxious material must have run directly into the Hudson River. Some of these pollutants might possibly still be there. Considering that in the late 19th and early 20th centuries there were no Superfund laws or stringent cleanup regulations, the pollution may still be around even though some of those industries are long gone. Although it is hard to know which sites may be polluted, this historical

information helps us predict the consequences of industrial land use.

|

Table 1. Top pollutants

currently being released in Poughkeepsie |

|

1) nitrate compounds 2) toulene 3) xylene (mixed isomers) 4) N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone 5) NH3 6) HF 7) methyl isobutyl 8) methyl ethyl ketone 9) HCl 10) H2SO4 11) HNO3 12) methanol 13) ethylbenzene 14) Zn 15) Pb compounds |

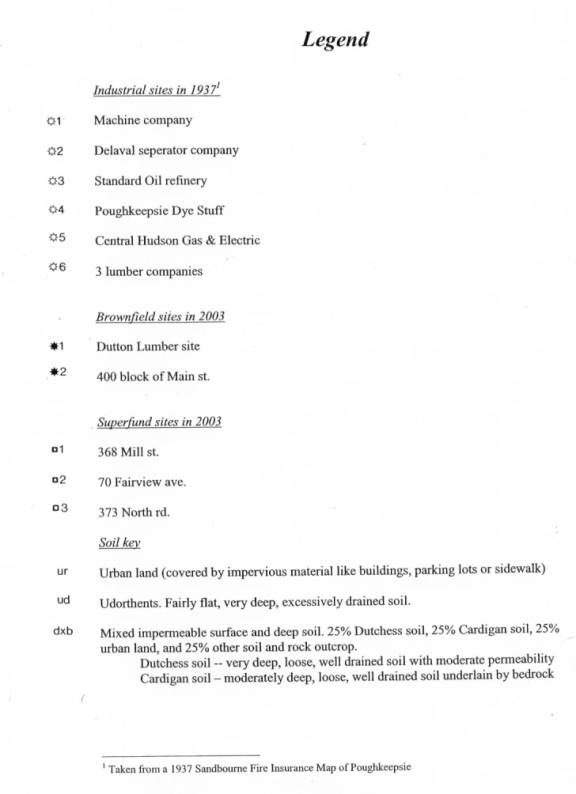

Current polluters

In addition to historical information, it is important to

think about current polluters, as those sites may someday become

brownfields. In Poughkeepsie, IBM releases 656,802 lbs. of toxic chemical releases a year,

Chemprene Inc. (a rubber band and miscelaneous. plastic manufacturing company)

releases 38,867 lbs. a year, and Great

Eastern Color and Lithographic Corp. (a printing and publishing company)

releases 8,160 lbs. a year. The major

pollutants being released in Poughkeepsie are known (Table 1), and keeping that

information accessible will help future brownfield reclamation efforts.

Brownfields defined

The EPA defines brownfields as

“abandoned, idled, or under-utilized industrial and commercial facilities where

expansion or redevelopment is complicated by real or perceived contamination”

(EPA, February 2003). This broad

definition allows many types of properties to be called brownfields and does

not make the term an official land use category. Former industrial sites are frequently identified as brownfields,

as are abandoned properties that have accumulated a lot of potentially

hazardous waste. Contamination in

brownfields can be visible (e.g., broken glass, metal scraps, pipes), or

invisible (e.g., arsenic, lead, etc. in soil and groundwater), and can have any

degree of severity. The EPA estimates

that 500,000 to a million brownfields exist in need of remediation in the

United States, most of them in urban areas (Concrete Products, 2002). Properties are most often identified as

brownfields when land changes hands, when someone expresses a public health or

environmental concern, and/or when a developer or local government wants to use

the available space.

Smart

growth policy

The interest in redeveloping

brownfields has political, environmental, and socioeconomic motives. Above all, redevelopment is a key objective

in the national push towards the revitalization of urban areas. Brownfield redevelopment can play an

important role in efforts to reverse problems such as suburban sprawl, farmland

loss, limited job and business opportunities in inner cities, and a lack of

urban recreational space. The benefits

of brownfield redevelopment are often underestimated in comparison with the

cost of greenfield development.

According to a report by George Washington University, every

acre of reclaimed brownfield saves 4.5 acres of greenspace (EPA, 2003a).

Brownfields often represent the only land available to redevelop within

city limits and therefore provides a potential supply of land for commercial,

industrial, and housing demands. Eyesores such as dilapidated factories

and vacant lots used as dumping grounds can be turned into job and tax creating

activities. Contaminated sites also pose

a threat to the environment and public health.

The cleanup and redevelopment of brownfields promotes infill over

sprawl, can improve environmental and health conditions in cities, and can have

positive impacts on struggling city economies. Since Dutchess County relies heavily on its

scenic tourist economy, Poughkeepsie might benefit from adopting smart growth

policies to reuse abandoned city sites in order to preserve its open space

resources.

Superfund sites and brownfields

Similarities between Superfund sites and

brownfields can lead to confusion of the two terms. The 1980 Comprehensive

Environmental Responses, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) is

referred to as “Superfund” and aims to identify responsible parties and require

them to bear the costs of contamination (EPA, 2003b). The cleanup of Superfund sites is driven by outrage over serious

contamination and Superfund policy mandates strict cleanup standards following

well-defined guidelines for the remediation process (Wernstedt, 2001). The program has been accused of being

inflexible and ignoring site-specific needs, but this inflexibility provides a

commitment to rigorous cleanup standards that brownfield remediation does not

always promise. On the other hand, brownfield cleanup programs are

carried out mostly by economic and social concerns over less severely

contaminated sites. Brownfields are mostly dealt with at a local rather

than federal level, and there is much greater flexibility in how remediation is

dealt with. In the past, Superfund laws

directly applied to brownfield sites although recently there have been some

policy amendments to ease the litigation involved in clean up and

redevelopment. However, money is often

lacking for cleanup since the EPA only funds brownfield pilot programs. Poughkeepsie’s difficulty in finding

investors for brownfields projects can be seen in its pending sale of the

Delaval Separator Company property to a private developer for only $1 (C. Woodhead,

pers. comm., 2003).

Liability,

Voluntary Action Programs, and incentives

In

response to reoccurring dialogues on health and environmental concerns, smart

growth policies, and city revitalization projects, the federal government has

created new legislation to encourage and facilitate brownfield

remediation. Acknowledging the market

potential and the environmental and social opportunities invested in cleanup

and redevelopment has been crucial to more comprehensive and effective

brownfield legislation. Above all, the

initiatives have been aimed at reducing the liability concern for individuals

or parties potentially responsible for contamination and increasing the support

for alternative programs and funding.

Together

with the EPA, the current administration has expanded the scope of brownfield

initiatives from the early days of 1995 when the first brownfield redevelopment

program was introduced (Ackerman, 2001).

Most recently in 2002, President Bush signed The Small Business Liability Relief and Brownfields Revitalization Act

in what was called “a great event for the environment in America” by the EPA

Administrator Christine Todd Whitman (Concrete Products, 2002). The

proposed goals are optimistic: to remove environmental hazards from

communities, to relieve pressure to develop open space, and to revitalize

communities by creating jobs and tax rolls. In addition to doubling the

funds for state and local programs available through the EPA to $200 million,

the bill grants liability protection for past, current, and future landowners

and prospective purchasers by relieving the liability constraints of federal

Superfund laws (EPA, 2003c).

The

legislation addresses liability as an important deterrent to brownfield

redevelopment. Indeed, the main

obstacle to redevelopment has been a liability concern for innocent landowners

and potential developers, even if they were not responsible for the

contamination. In part because of the strictness of Superfund’s

assignment of responsibility to all current and former owners of contaminated

sites, the threat of liability and unforeseen costs has hindered a confidence

and willingness to engage in brownfield redevelopment. Policy amendments are often based on the

belief that reducing liability burdens will instill more confidence to

participate in potential redevelopment projects if financial incentives offset

environmental liabilities.

Nevertheless, the long term success of this program will depend on how

effectively liability is redirected.

Furthermore,

brownfield legislation has sought to encourage innovative cleanup programs as a

way of bridging the gap between the role of the federal government and state

authorities, local governments, and individuals interested in

redevelopment. The EPA manages State Voluntary Action Programs to allow

private parties or volunteers to initiate the identification and cleanup of

sites. Voluntary participants can avoid

the lengthy administrative procedures usually encountered in site assessment

and remediation. Protection from liability and future federal and state

enforcement actions comes through “no further action” letters, whereby the EPA

promises not to become involved if certain guidelines are followed (EPA,

2003d). Besides being a huge incentive against extensive litigation,

voluntary programs aim at increasing community involvement in brownfield

programs by allowing residents to play an active role in assuring that

remediation and redevelopment respond to wider community goals. Neighbors may have more of a say as to whether

a playground, community center, housing project, or industrial factory is

redeveloped on the site. Since

community members tend to be the most concerned with environmental and health

threats, the ability to oversee and mediate cleanup and redevelopment projects

is to their benefit. In addition,

voluntary programs cut short the delay in relying on the federal government to

take action and reduce developers’ reluctance to buy properties. Such alternative programs have made possible

numerous redevelopment projects in 44 states and have been successful in

increasing active participation in brownfield cleanup and redevelopment.

Legislation

has also encouraged the creation of partnerships to facilitate mutual goals and

support investment. Since brownfields play a role in public health,

environmental protection, transportation, economic development, and community

revitalization, the support of these groups is essential for the successful

management of brownfields programs. One example is the opportunity for

adoption of remediation into other community projects. Such is the case with the EPA’s “Green

Buildings on Brownfields” program and its partnership with Habitat for Humanity

to build energy efficient houses on former contaminated sites (Ryan, 2002).

Incorporating brownfields into greenway plans is another way of building

partnerships among groups with similar agendas. For example, the planners of the Woonasquatucket River

Greenway Project in Providence, RI were able to incorporate severely

contaminated brownfields into the greenway’s route (Braswell, 1999). The

project became a Brownfields Showcase Communities project, with EPA funding to

go with it. The remediation has brought

an ecological focus to the greenway project, and has allowed the plans to attract

much more support. National and local

attention has been brought to the project, and neighbors have been delighted to

support the greenway. This

type of cooperation can benefit all parties, and legislation has sought to

maximize it. Encouraging cooperation

with environmental and community organizations in Poughkeepsie has the

potential to speed brownfields redevelopment and increase satisfaction with the

results. Strong non-profit

organizations and a variety of planners of city greenways make up a large

sector of involved citizens who could become more interested in brownfields

reclamation if the connection to their goals were clearer. Scenic Hudson’s possible involvement with

the purchase of the Dutton Lumber site is a local example of different parties

and interests coming together to remediate a brownfield site and link up with

the greenway plan.

Site assessment & remediation

One of the main concerns of developers is

how to maximize site value while minimizing cleanup cost. The sites that have

the greatest potential for profit, and therefore are the most desirable to

developers, include sites near a waterfront, commercial, or business district,

and sites that are easily accessible by public transportation or by major

roads. Governments and developers are

generally more reluctant to clean up other sites. Sites that are seen as low priority to governments and developers

include smaller, less accessible brownfields in deteriorated

neighborhoods. Location and

marketability determine the development priority of sites when the redevelopment

is motivated by profit-generation. It

is not surprising that recently completed brownfield remediations in

Poughkeepsie are all found either along the waterfront or on Main Street.

Once a government or developer has

focused on a site to work on, the process can begin. However, the initial assessment of a site can take a long time

and cause the project to stagnate.

Before remediation can start, the government or the developers must

assess the extent of the pollution and how far it has spread. One of the main ways that pollution can

spread from a brownfield into surrounding areas is by way of groundwater. If the soil in the brownfield is very

permeable (i.e. sand or gravel) and the aquifer is unconfined (meaning there is

no thick layer of bedrock keeping it from connecting with overlying soil),

there is a good chance that pollutants in the soil have reached the

groundwater. However, there may not be

any groundwater underneath that particular site. The vulnerability of the groundwater must be assessed by

combining data from a surface geology map with data from an aquifer map

(Appendix 1). Vulnerable groundwater

makes remediation difficult and always makes the cost of cleanup high.

Even with no significant groundwater

vulnerability, other problems can make remediation costly. The former use of a site determines what

contaminants are present, so looking at the historical use can help with the

assessment. There are four classes of

common contamination: heavy metals, chlorinated hydrocarbons, petroleum

hydrocarbons, and PCB’s. Heavy metal

contamination is commonly found at former industrial, utility, and

manufacturing sites. The sites of

several 1937 lumber companies on Poughkeepsie’s waterfront may have this type

of contamination. Chlorinated hydrocarbons

are often detected at sites previously used for the coal industry, primary

metal industry, and manufacturing of industrial machinery or equipment. A machine company that existed in 1937

(Figure 1) could have released chlorinated hydrocarbons in Poughkeepsie that

may still be there. Petroleum

hydrocarbons are found mostly in old chemical and petrochemical sites. They are

also common in industries involved in the manufacturing of rubber, and

miscellaneous plastic products. The

Standard Oil refinery and Central Hudson Gas & Electric sites (Figure 1)

probably left these behind. PCB’s are

not linked to any one type of site, but statistically they are more likely to

be found in sites owned by the government (Stiber et al, 1998). Associations between industries and the

pollutants released allow chemical testers to make informed guesses about

contamination and use the most appropriate testing method (Appendix 2).

The traditional method of testing, which

is still advocated by the EPA, is extremely time consuming and costly. It involves taking large soil and water

samples through the drilling of trenches or wells. Once the samples are extracted, they are sent to a lab where comprehensive

tests are performed. The results of these tests could take up to two months and

cost thousands of dollars. If the test results are somehow inconclusive (the

type of pollutants expected were not present in significant amounts), or if

more samples are needed, a return investigation is often necessary. This alone could cost from $20,000 to

$500,000 (Munro et al, 2000). A number

of new, portable technologies are available to make initial testing less time

consuming and expensive (Appendix 2). These

methods can be more quickly done on site and can test for many things at once

without the huge costs of lab work.

Unfortunately, though, only 6% of EPA funded brownfields projects are

using these methods (Munro et al, 2000).

The EPA continues to recommend the traditional testing method,

preferring to rely on what has worked in the past rather than risking working

with new technology. Also, information about new technologies is not easily

available to community members, municipalities, and others involved in

brownfield redevelopment, so informed choices about which methods to use are

hard to make. The continued use of

costly, inefficient methods adds to brownfield redevelopment barriers.

Once the type and location of the

contamination has been assessed, remediation options can be discussed. The

remediation method used depends primarily on the type and extent of

contamination - mainly whether or not it has reached any groundwater. The high cost of remediation is another

barrier to redevelopment, but in some cases, unnecessarily stringent clean up

standards are used. The clean up should

not only reflect the risk of the site, but also its intended future use. For example, a site that has not

contaminated any groundwater and is intended for future industrial use does not

need to be cleaned up as thoroughly as a site that is going to be used as a

playground. If the contaminants will

not harm people, wildlife, or groundwater, they don’t need to be cleaned up

quite as carefully. Noxious chemicals

have to be cleaned up whatever the future land use, because even if people

around it aren’t affected, vegetation might be. Heavy metals, specifically Cd, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Zn, although once

thought to be harmful to plants, were found not to have any significant affect

on vegetation or soil processes even with relatively high levels of metals. A site contaminated with heavy metals that is

going to be used for industrial purposes and that poses no significant risk to

groundwater needs barely any remediation, and will not cost much to redevelop

(Murray and Henderson, 2000). This is

an area where the flexibility given to municipalities in determining cleanup

standards can save money without risking public health.

Environmental Justice & Community Involvement

Legislation and incentives designed

to stimulate brownfields reclamation have been advertised primarily in terms of

their economic potential. For the

public, the generation of jobs and taxes is the attraction; for developers and

investors it is profit. While finding

ways to lower barriers to brownfields redevelopment is a good goal for cities

with unused space, some authors have questioned the ability of programs that

are driven by economic considerations to maintain a commitment to the

neighborhoods in which the sites are found (McCarthy, 2002; Kibel, 1998;

Davies, 1999). Concerns about justice

in making and carrying out brownfields redevelopment plans seem to appear

frequently in brownfields literature, so it is important to consider how equity

can be promoted.

The Environmental Justice movement

seeks to create equal access to environmental resources and equal protection

from ecological hazards for all communities.

It is a movement that gained political prominence at around the same

time as brownfield redevelopment programs did and the Clinton administration

was very interested in presenting the two as compatible (Kibel, 1998). A series of public discussions called

“Public Dialogues on Urban Revitalization and Brownfields: Envisioning Healthy

and Sustainable Communities” was held in five cities to try to gauge public

response to brownfields initiatives and to incorporate the desires of community

members into the development of legislation.

Incorporating the wishes of many participants proved to be difficult,

but the desires that were revealed most clearly in those discussions were that

brownfields plans improve the public health and economic well being of the

surrounding community.

In contrast to the strictly held

cleanup standards of Superfund sites, brownfield remediation standards are left

to local governments to enforce, allowing flexibility in planning but also

leaving the possibility for dissatisfaction with varying degrees of remediation

(Davies, 1999). Voluntary cleanup

programs and liability waivers can reassure investors and developers that a

project is worth their time, but these programs have also been accused of

allowing oversights in cleanup efforts and overprotecting those at fault. Lower remediation standards may seem to be

the only option to a town having difficulty convincing anyone to invest in an

undesirable property. It is important,

therefore, for a municipality that is dealing with brownfields to develop

standards that can be applied to all sites.

Creating standards on a case-by-case basis leaves too much potential for

injustice to lower-income communities.

The difficult balance between leaving enough flexibility to encourage

interest in brownfields while maintaining enough strictness to ensure the fair

application of cleanup levels.

The allocation of funding to

brownfields is an area where the potential for real and perceived injustice is

great. Through the EPA’s Pilot Program,

municipalities are encouraged to choose demonstration sites that will stimulate

private interest in brownfields by showing the benefits of a successful

reclamation (McCarthy, 2002). Funding

is provided for the demonstration site, but not for projects beyond that, so

the choice of site plays a large part in determining whether the Pilot Program

will work. The goal of creating large

amounts of interest in brownfields is a good one, but this program has the

potential to use public funding for properties that may have been economically

viable without help, leaving less desirable properties without the public

funding they need. In choosing the

sites of brownfields demonstration projects, municipalities should ensure that

the project has a good chance of success in generating interest, but they

should also be careful not to fund properties that don’t need assistance.

The potential for economic injustice

continues after the allocation of funding is resolved; the use of the

revitalized brownfield can be quite controversial. Jobs may be generated at former brownfields, but there is no

guarantee that jobs will go to area residents, and the use of a site to most

benefit people from outside the neighborhood can create resentment. Some cities have tried to encourage

satisfaction with the use of brownfields by creating tax incentives for loans

made to local small businesses (Kibel, 1999).

Others have favored projects with tangible health and economic benefits

for the community in which it takes place.

Brownfields neighbors respond to

proposed projects with enthusiasm as well as concerns. The benefits to the neighborhood can be very

attractive, and many neighbors are eager to see unused land go to good

use. The crucial factor in whether or

not neighbors will be satisfied with a brownfields project is the degree to

which they are involved (Davies, 1999).

The involvement of community members can also make the process of

remediation faster and more effective – a study of EPA pilot projects concluded

that community involvement is not only fair, it is “a mechanism for faster,

better cleanup and redevelopment” (Davies, 1999). Neighbors have access to useful, site-specific knowledge that can

be tapped into with meaningful involvement.

Municipalities and developers may have trouble finding routes for local

involvement, but both can take steps to encourage it. Municipalities can work with existing neighborhood groups during

the selection of a developer to ensure that the project will be desirable, and

can conduct polls prior to deciding on a project. During the development process, planners can be required to

create easy-to-read materials and make them widely available to neighbors

(Zarcadoolas, 2001).

Access to information via GIS

Information about brownfields is often difficult to access,

both for interested neighbors and for developers and investors who might be

interested in brownfields. In response

to the scattered information available, some authors have suggested gathering

information in a GIS-based decision support system that would be available for

many interested parties to use (Thomas, 2002).

The city of Emeryville, CA has done this; an online GIS system has been

created that allows anyone to look at city maps and get information about

things like the owner, value, and current land use of a give property (Appendix

3). This new way of keeping a variety

of parties informed may become very useful in solving some of the difficulties

associated with redevelopment.

Conclusion

Brownfields can pose economic,

health, and social problems, but they can also be considered resources that can

create new spaces in crowded cities and generate economic activity on

previously abandoned land. The way a municipality goes about the process of

reclamation can make all the difference between successes and failures. Hopefully, more cities will make centralized

information available to those interested in brownfields, and will make better,

more informed decisions about how to redevelop, and planners will continue to

become more interested in reclaiming brownfields.

Works Cited

Ackerman,

J. 2001. Finding your brownfield of dreams. Waste Age 32:166-73.

Braswell,

B.J. 1999. Brownfields and bikeways: making a clean start. Public Roads

62:32-40.

______. Concrete Products. 2002.

Brownfield legislation spurs ‘green’ business.

Concrete

Products. 105: PC6-PC8.

Davies,

L.L. 1999. Working toward a common goal?

Three case studies of brownfields

redevelopment

in environmental justice communities.

Stanford Environmental

Law

Journal 18:285-329.

Environmental

Protection Agency. 2003a. Brownfields Cleanup and

Redevelopment.

<http://www.epa.gov/swerosps/bf/htm>

accessed April 2003.

Environmental

Protection Agency. 2003b. Glossary of Terms.

<http://www.epa.gov/swerosps/bf/glossary.htm#brow>

accessed February 2003.

Environmental

Protection Agency. 2003c. Small

Business Liability Relief and

Brownfields

Revitalization Act.

<http://www.epa.gov/swerosps/bf/sblrbra.htm>

accessed March 2003.

Environmental

Protection Agency. 2003d. State Voluntary Cleanup Program

Guidance

History.

<http://www.epa.gov/swerosps/or.vap_hist.htm>

accessed April 2003.

Greenberg, M. et

al. 2001. Brownfield redevelopment as a smart growth option in the

United

States. The Environmentalist

21:129-143.

Kibel, P.S. 1998.

The urban nexus: open space, brownfields, and justice. Boston

College

Environmental Affairs Law Review 25:589-618.

McCarthy,

L. 2002. The brownfield dual land-use policy challenge: reducing barriers

to

private

redevelopment while connecting reuse to broader community goals. Land

Use

Policy 19:287-296.

Munro, J. F.,

and K. A. Tzoumis. 2000. Conquering the brownfields frontier through

the

enhanced

deployment of environmental assessment technologies. Public Works

&

Management Policy 4:213-221.

Ryan, D. 2002.

EPA Administrator announces brownfields program partnership with

Habitat

for Humanity International. Environmental

News, Environmental

Protection

Agency.

<http://www.epa.gov/swerosps/bf/html_doc/pr021302.htm>

Stiber, N. A.,

M. J. Small, and P. S. Fischbeck.

1998. The Relationship between

historic

site

use and environmental contamination. Journal

of the Air & Waste

Management

Association 48:809-818.

Thomas, M.R.

2002. A GIS-based decision support

system for brownfield

redevelopment. Landscape and Urban Planning 58:7-23.

Wernstedt,

K. 2001. Devolving Superfund to Main st. – avenues for local community

involvement. Journal of the American Planning

Association, 67:293-313.

Zarcadoolas,

C. 2001. Brownfields: a case study in partnering with residents to develop

an

easy-to-read print guide. Environmental

Health 64:15-20.

Figure 1.

Brownfields, Soils and Historic Industrial Land Uses