Greenway

Development and the national Park Service:

The

Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Vanderbilt Mansion Historic Sites

This paper is an analysis of the National Park Service’s role in creating greenways in Dutchess County. Through a multi-dimensional approach that describes ht historical significance, ecological impacts, and the management role of the National Park Service, a more developed understanding of the Park Service’s role in the greater Hudson River Valley Greenway will be gained. A map of the area’s land ownership, soils, and historic sites will help to visualize greenway development in Hyde Park.

Rachel Alkire, Ramone Lopez, Sam Marquand, and Ada

Montague

Table of Contents

1. Greenways and The National Park Service

2. Setting the Stage: The National Park Service and Greenways in Hyde Park

a. How the NPS Works to Create Greenways

b. The Hyde Park Trail and Val-Kill Extension

3.

Historic Overview and

Cultural Importance of the Vanderbilt and Roosevelt Sites

- The Establishment of the Hyde Park Trail

- Who Is the Hyde Park Trail For?

- Is

biodiversity at risk as a result of greenway development?

- An example of green space development working to preserve

biodiversity

- An environmental ethos at work in Sweden

- Guidelines for biodiversity-friendly development

- Caution is critical

- The Big Picture: The Hudson River Valley Greenway

- Figures

- Bibliography

I. Greenways and The National Park Service

The National Park Service is critical but limited in its ability to create greenways in Dutchess County. The Hudson River Valley Greenway, which began in 1988, is an enormous project involving the twelve counties lining the Hudson River between New York City and Albany. The fourteen years since the project’s commencement attest to the slow and difficult process of aligning the necessary support and resources required in greenway building. The National Park Service (NPS) is instrumental in this process, serving to foster partnerships, accumulate land, and educate interested citizens. On the other hand, their efforts are curtailed by the legal boundaries of the parks they manage.[1] However, they remain instrumental in creating trails and local partnerships, and they are committed to supporting the larger Hudson River Valley Greenway. Their role in the connection of The Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site and the Franklin Delano Roosevelt National Historic Site through trails demonstrates two things: the role of the National Park Service in developing greenways, and the intricacies of the process.

This greenway analysis will examine the Hyde Park Trail, which connects the Vanderbilt and Roosevelt estates, and the Val-Kill Extension, which connects Roosevelt’s main house to the Val-Kill Cottage. To better understand how greenways develop from a concept into reality, we will begin with a discussion of the NPS’s work to create greenways at the three sites through partnerships and collaboration in Hyde Park. A historical review of each site will follow. By investigating the cultural value of the area, we will demonstrate how its preservation fulfills the rationale behind the Hudson River Valley Greenway, which is to preserve cultural as well as natural landmarks. Having established the role of the NPS in creating greenways in Hyde Park and the importance of their efforts, understanding the natural impacts of the process will carry our knowledge of greenways beyond the anthropocentric. A thorough understanding of the biology and geology of the area will help investigate environmental impacts of these greenway efforts. Through our analysis of greenway development we have investigated the NPS’s method of greenway building in Hyde Park, its cultural significance, and its ecological impacts. In conclusion we will relate these local processes to the broader, inter-county effort to create the Hudson River Valley Greenway. Our aim in putting together this document is to demonstrate how the NPS is involved in greenway creation.

II. Setting the Stage: The National Park Service and Greenways in Hyde Park

The NPS in Hyde Park is helping to

make the Hudson River Valley Greenway a reality. Oftentimes government agencies are not as supportive in

protecting against destructive development as the NPS in Hyde Park. Gustanski and Squires (2000) explain the

frustration with government agencies in their book Protecting the Land:

Conservation Easements Past, Present, and Future. They claim that, “Despite the efforts of countless planning

commissions and local and regional government agencies, many people across the

county have become frustrated and disillusioned by the failings of various

government programs to adequately protect cherished lands from sprawling

development” (Gustanski and Squires 2000). In sharp contrast to this complaint, the NPS

has created important local collaborations organized around building trails in

Hyde Park. Through an analysis of the

NPS’s role in Hyde Park we will better understand how the plan for a greenway

becomes a reality.

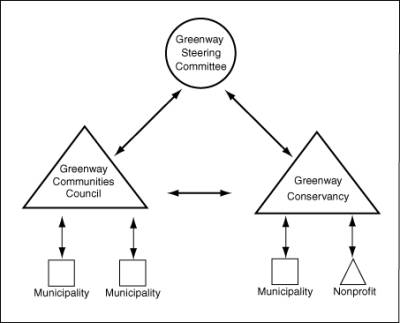

A. How the NPS Works to Create Greenways

The National Park Service is active in Hyde Park as a generator of partnerships, which help to bring together land and money for trail development. The Vanderbilt and Roosevelt estates were connected with the establishment of the Hyde Park Trail, which runs along the Hudson and could provide a model for future Hudson River Valley Greenway initiatives. The cultural resource of Val-Kill, Eleanore Roosevelt’s cottage, 1.5 miles east of the Roosevelt estate, is connected via the Val-Kill Extension Trail. The NPS formed partnerships with Winnakee Land Trust, Scenic Hudson, the Town of Hyde Park, Adirondack Mountain Club, and a cooperation of private landowners to make these trails (Figure 1) (Hayes 2003). Their attempt to link the Hyde Park Trail to Norrie State Park is at an impass due to the unwillingness of residents. These landowners fear an invasion of their privacy by the trail as well as potential liability issues. In order to assuage these worries, the NPS and its partners have come up with a “Voluntary Trail Agreement,” which serves to delineate the type and nature of the trail and relieve residents of legal responsibility (Figure 2) (Hayes 2003). It is through such cooperation and creativity that the greenway will eventually become a reality.

B. The Hyde Park Trail and Val-Kill Extension

The NPS’s current trail building project within its own property on the Roosevelt Site is the creation of a tourism information center that will serve to connect the three sites. A $1.5 million grant was awarded to the partnership working on this project, and will go to the building of a parking lot and information center just across Route 9 from Roosevelt’s former home (Hayes 2003). The center will serve as a starting and organizing point for interested visitors. After getting oriented and educated, tourists will be able to take high-energy efficiency vehicles to the sites that interest them. Ideally this will localize information distribution and center the tourist experience. The creation of a road on the current Val-Kill Extension Trail is in process to connect Val-Kill to the proposed tourism center. The development of a road in this area will make the functioning of the parks more centralized under the NPS’s control and may streamline the tourist experience.

III. Historic Overview and Cultural Importance of

the Vanderbilt and Roosevelt Sites

The town of Hyde Park features the Vanderbilt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Sites. The Vanderbilt site lies north of the Roosevelt sites along the Hudson (Figure 3). In 1895 Frederick Vanderbilt and his wife Louise bought the 600-acre acre property, which was then simply referred to as Hyde Park and constructed an impressive mansion. When Frederick died in 1938, his wife having passed away ten years earlier, Louise’s niece Margaret van Allen inherited the estate, which she generously donated to the Federal Government (NPS, 2001). It became a National Historic Site in 1940 (NPS, 2003).

The Franklin D. Roosevelt site lies directly south of the Vanderbilt site on the Hudson River (Figure 3). Franklin’s father purchased the property, which is traditionally referred to as Springwood, in 1867. When FDR died in 1945, he was buried in the rose garden there (NPS & NY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, 2001). Springwood became a National Historic Site in 1959 (NPS, 2003). The Eleanor Roosevelt site, also known as Val-kill, is directly east of the FDR site (Figure 1). Because Eleanor wanted to enjoy the area year round and in the absence of her husband, the Roosevelts purchased Val-kill in 1925. Eleanor died in 1962 and Val-kill was sold in 1970. After private landholders expressed development interests in the property, it was decided that the land was of significant cultural importance and should be protected. The site was bought back by the federal government in 1977 and established as a National Historic Site shortly thereafter (H. Johaneson, pers comm).

A. The Establishment of the Hyde Park Trail

The Hyde Park Trail is a system connecting these National Historic Sites and several parks. It showcases both the rich heritage of Hyde Park and the beauty of the Hudson River Valley. Collectively the trails are 8.5 miles in length and are managed by the Adirondack Mountain Club, Mid-Hudson Chapter; Boy Scouts of America, Dutchess County Council; National Park Service, Roosevelt-Vanderbilt National Historic Sites; The Scenic Hudson Land Trust, Inc.; Town of Hyde Park; and Winnakee Land Trust, Inc (NPS, 2002). On-site trail signs indicate the National Park Foundation, the Hudson River Improvement Fund, and Greenway Heritage Conservancy provided the most of the funding for these trails.

The

idea for such a trail system was initially put forth by the National Park

Service in 1977. Their focus was the

stretch of land along the Hudson connecting the Vanderbilt and FDR sites. This land also crosses through the

Riverfront Park, which was established in 1968 after the Town of Hyde Park

bought the old New York Central Railroad Station (NPS, 2002). The trail did not actually come to be until

1984, when a group of Vassar students collected the necessary information and

produced a map depicting land ownership and a potential trail route (Scenic

Hudson & NPS, 1989). Since then

several other trails have been established, most notably the Val-kill Trail,

which is actually an old carriage road, connecting the Franklin and Eleanor

Roosevelt sites. It is also currently

the only trail that allows bicycles (NPS, 2002). National Park Service

employees have indicated that long-term plans might include a trail connecting

Val-kill to the Vanderbilt site.

B. Who Is the Hyde Park Trail For?

While on-site National Park Service employees have estimated unofficially that over one million people visit the Vanderbilt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic sites annually, they believe local residents primarily use the trails. This reflects an important link that the Hyde Park Trail creates between these sites and the community. Tourists generally drive from site to site or take tour buses, and the National Park Service is doing little to promote tourist use of these trails. However, an effort is being made to centralize the tourist experience of the National Historic sites. Recently Hyde Park officials, residents, and business owners joined forces with the National Park Service to form the Belfield Group. It was their collective effort that secured the 1.5 million-dollar grant to build a larger parking lot at the FDR site and pave the Val-kill trail so there is a direct road between the two sites.

Although

the Bellfield Group represents a wide variety of interests, it must be question

whether plans for these trails adequately incorporate the interests of the

locals who use them the most. The

Val-kill Trail is the only trail for bicycles, but in the near future cyclists

may have to compete with tour buses.

This seems unfair to Val-kill Trail users considering that existing

roads already allow for a speedy trip between sites. Indirect routes between sites also serve to connect tourists to

the Town of Hyde Park and promote local businesses. On the other hand, the Belfield Group’s development plan does

allow the National Park Service to focus their park operations and presumably

enhance the tourist experience. In the

future the Hyde Park Trail will be connected as a part of the larger Hudson

Valley greenway plan and tourist traffic is likely to increase. This is a

critical incentive to promote environmentally conscious trail management.

IV.

Is biodiversity at risk as a result of greenway development?

The proposals for the Val-kill loop, including development

of trails, as well as a parking area and road system for ferrying visitors from

point to point within the park system, could have severely negative impacts

upon the area’s local wildlife.

Advanced development, green or not, is risky from a biodiversity

perspective, and will require careful monitoring if the biological systems that

are currently in place are to be sustained or improved. It is important to understand that, as

Miller and Hobbs (2000) explain, “Although both recreation and wildlife

conservation are commonly emphasized in greenway management plans, the compatibility

of these two activities remains poorly understood. Outdoor recreation has been shown to harm most native species

that have been studied, suggesting that a dual

emphasis on conservation and recreation may be more a marriage of convenience.”

A. An

example of green space development working to preserve biodiversity

In order to see the potential for the

success of green space in the preservation or increase of biodiversity, it is

important to look to current ecological research. One study by Mörtberg and Wallentinus (2000), attempted to assess

the success of green space corridors around Stockholm using IUCN red-listed

forest birds as an indication of the health of the environment. The idea was to determine whether or not it

was possible for the forest remnants that surround that city, along with green

space corridors, to support target species for conservation. They found red-listed forest birds breeding

within the area and found a substantial connection between the vegetation, soil

type and plot size of the particular areas and the numbers and diversity of

bird species present. They surmised

that the green-space in this scenario, which features large plots of land

linked by continuous habitat, was beneficial because it was mostly mature

deciduous forest, meaning that the forest was able to age and decay in a proper

manner because it was not subject to the levels of deforestation prevalent in

more rural areas. The conclusion of

this study was cautious, and indicated only that, in this particular area,

large, undisturbed plots of deciduous forests were ideal for the most sensitive

species in the region.

B. An environmental ethos at work in Sweden

Alexander Ståhle (2002) explains that Stockholm has experienced this level of success precisely because the management of its green space has been so good and the emphasis on green development and green infrastructure has ensured that nature has a stake in development. The development strategy employed in Stockholm was developed by Mr. Ståhle and a colleague, and is known as the “sociotop.” This concept is derived from the accepted scientific “biotop,” which refers to the ecologically defined environment. Under this philosophy, green space is stressed as a cleaner of air, a place for socialization, a place to maintain cultural history and to learn about, and nurture, the natural world in a world “dominated by the computer screen” (Ståhle 2002). His report also outlines the importance of parks and reserves and the new ethos demands that everyone in the city should have a block park (1-5 hectares in size) within 200 meters, everyone should have a city district park (5-50 hectares) within 500 meters and that everyone should have a nature reserve (>50 hectares) within one kilometer of their residence.

C. Guidelines for biodiversity-friendly development

These kinds of developmental guidelines

are made possible by an ethos that has not yet taken root in the United

States. Most people would be surprised

to know that there are many threatened and endangered species living in the

Hudson River Valley region. Chances are

that some of these species inhabit the regions protected as National Monuments

by the National Park Service. As Hudsonia

Ltd’s (2001) “Biodiversity Assessment Manual” stresses, there are several

points to consider when planning the conservation of green space if

biodiversity is a major concern. It is

important to conserve mature biological systems, as seen in the above example

of Stockholm, because they are more pristine and, as a result, more

functional. Human use must be directed

towards areas that are less sensitive, and surfaces paved with impervious

substances must be minimized. For

example, in the Val-kill loop it would be important to keep development away

from riparian areas, and the paving of a trail through this area, part of which

is located at the tip of a large watershed (see attached map GET MAP #), will

likely increase harmful runoff into these aquatic systems. Simply developing riparian areas by removing

vegetation or using impervious materials would likely increase the pollution

load in the local streams and ponds and critically disrupt these systems. One endangered species whose habitat is

rapidly diminishing as a result of these kinds of problems in the Bog Turtle,

whose habitat, fens and wet meadows, have been so degraded in many areas due to

increased influx of nutrients, silt and increased growth of tall shrubs and

trees. It is now listed as endangered,

both in New York State and federally.

Vegetative buffer zones along waterfronts can drastically minimize the

negative effects of riparian development.

Plants are remarkably capable of preventing the pollution of the water

source to which they stand adjacent

(Hudsonia Ltd. 2001). Another

key point is that large parcels of relatively untouched land must be saved from

development. Small pieces of land

support progressively less and less biodiversity. The Hudsonia manual also stresses that preservation of migration

corridors can be just as important as preserving the area where a particular

species performs its primary foraging or breeding, driving home the point that

habitat fragmentation can be extremely damaging.

D. Caution is critical

The need for caution in developing natural areas, even in a green manner, cannot be overstated. While there are people working for the National Park Service, such as Karl Beard, one of the scientists involved in planning, for whom the question becomes, “If not this, then what?”, it is important to remember how delicate natural systems are. There is no use in preserving land, saving it from development as a sub-division or a shopping center, and then paving it over with roads and parking lots, and fragmenting it with recreational trails. The end effect will be essentially the same in either of these scenarios. The sensitive species, the Bog Turtles and Rattlesnakes, will be lost and the landscape will come to be dominated by edge-effect generalists and invasive species such as gray squirrels, crows, purple loosestrife and tree-of-heaven. If preservation of native, sensitive species is a priority, then it is necessary for development, if it is to go forward, to be slow and open to change, with research scientists involved every step of the way.

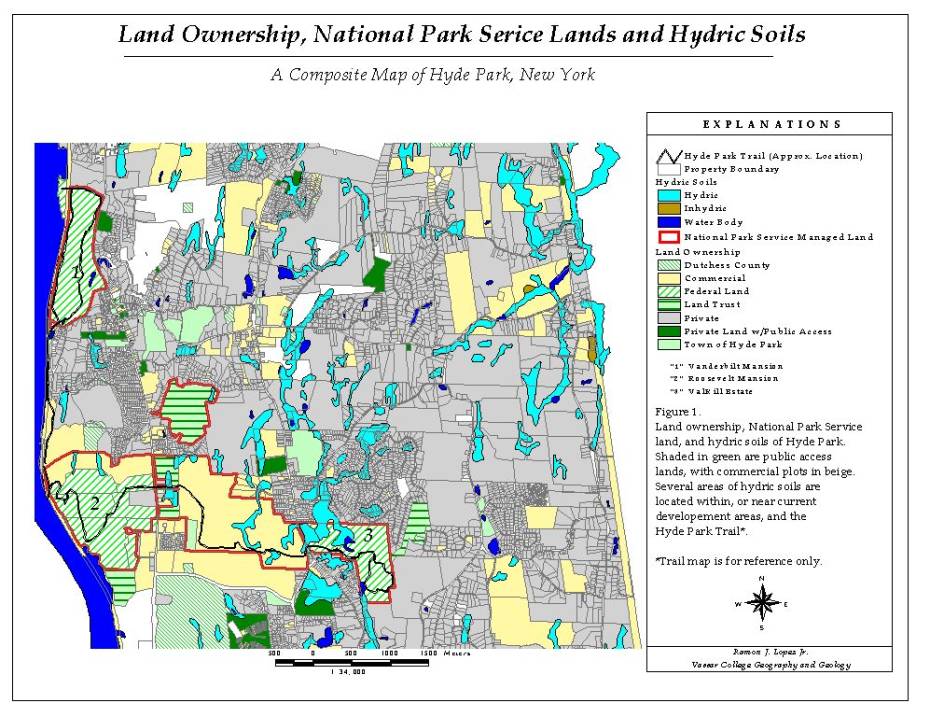

V. The Big Picture: The Hudson River Valley Greenway

Greenway development on a statewide scale has been underway since the late eighties. In April 1989, then Governor Mario Cuomo proclaimed, “I want the Greenway to be an emerald necklace, a legacy. I want them to say Mario, the Greenway.”[2] A group of experts, the Hudson River Valley Greenway Council, was organized to develop a proposal that made recommendations and arguments for the greenway. They recommended the formation of a voluntary Hudson River Valley Compact between the 82 towns, villages, cities, and boroughs that line the Hudson from the Mohawk River to the Battery in New York City. They also asked New York State to define the greenway as a geographical entity, and that it be reflected in signage and tourism promotion (Figure 4). Next they advocated the creation of a “Greenway Conservancy” to provide funding and technical assistance. Finally, they decided that a Hudson River Trail, to run on both sides of the Hudson River, was the ultimate goal of the greenway initiative.

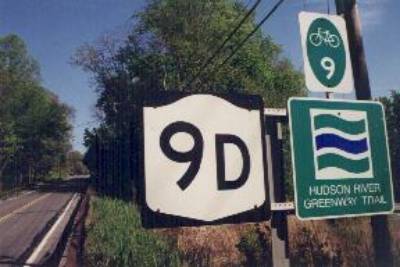

The Council’s suggestions were realized, and now all decisions made within and regarding to the greenway are authorized through the Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area. The Council is in charge of all policy and planning and functions to formulate and adopt the greenway framework. The Conservancy is concerned with the implementation and functions as a land trust, working directly with local municipalities, non-profits, and partnerships. All managing bodies recognize the importance of localized initiation for the project’s success (Figure 5). Lt. Governor Stan Lundine argues, “But above all, it’s a locally generated regional effort that will allow the people of the Hudson River Valley to preserve the best of the past while planning for the future” (Hudson River Valley Greenway Council 1991).

The NPS has proved itself vital to the development of a Hudson River Valley Greenway project. They are active in preserving the important historical sites of the Vanderbilt and Roosevelt estates. The tourism generated by these places is critical to the rationale behind the Greenway to celebrate cultural and historical landmarks. Locally the greenway efforts of the NPS provide residents with important access to open space. Ecologically the NPS must remain aware of the pending issues that arise with road and trail construction, such as habitat fragmentation and degradation. Aquatic habitats are particularly at risk because of increased runoff from impervious surfaces. Monitoring their progress as they go will help the NPS remain abreast of any serious ecological impacts. The geology of the area … The NPS has proven invaluable in forming partnerships and organizing the local community. However, they are limited in their ability due to the stipulations on the original gifts of land. Our analysis has led us to believe that National Park Services can be extremely useful in motivating greenway efforts by providing organization and links to the community and to tourism. Their efforts in Hyde Park are making the Hudson River Valley Greenway project a reality.

Bibliography

- Albee, P.A. Historic Structure Report Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Massachusetts: 1996.

- Boniello, K. & K. McLaughlin. “Hyde Park Honors FDR’s Birth, Life.” Poughkeepsie Journal: Jan. 31, 2003. BO3

- Cook, E.A. “Landscape structure undicies for assessing urban ecological networks.” Landscape and Urban Planning. 2002. Vol. 58, No. 2-4, page 269-280.

- Cranz, G. The Politics of Park Design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1982.

- Davis, J. “Hyde Park Talking to Landowners.” Poughkeepsie Journal: Jan 22, 2003. BO3

- Farmer, Anthony. “ Sweeny secures cash for Hyde Park tourism.” Poughkeepsie Journal: Feb. 14, 2003. BO3

- Gustanski, Julie Ann and Roderick H. Squires. Protecting the Land: Conservation Easements Past, Present and Future. Island Press: Washington, DC., 2000. Page 17

- Guglielmino, J. “Greenways: paths to the future.” American Forest, vol. 103, Autumn, page 26-27.

- Hayes, David. Park Coordinator for Vanderbilt and Roosevelt National Parks. Interview: March 28, 2003.

- Hudson River Valley Greenway Council. A Hudson River Valley Greenway: A Report to Governor Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. New York State Office of General Services: New York, 1991.

- Hoctor, TS, MH Carr and PD Zwick. “Identifying a linked reserve system using a regional landscape approach: The Florida ecological network.” Conservation Biology, vol. 14, no. 4, pg. 984-1000.

- Johaneson, Harry (tour guide for Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site). Interviewed March 29, 2003 at Val-Kill.

- Leitao, AB. And J. Ahearn. “Applying landscape ecological concepts and metrics in sustainable landscape planning.” Landscape and Urban Planning. 2002, Vol. 56, No. 2, pg. 65-93.

- Little, CE. “Making greenways happen.” American Forest. 1989, Vol. 95 (Jan/Feb), pg. 37-40.

- __________. “Linking countryside and city: the uses of greenways.” Journal of Soil and Water Conservation. 1997, Vol. 42 (May/June), pg. 167-169.

- Machlis, G.E. & D.R. Field. Naitonal Parks and Rural Development. Island Press: Washington DC., 2000.

- Marzluff, John, Reed Bowman, and Roarke Donnelly, eds. Avian Ecology and Conservation in an Urbanizing World. Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, 2001.

- Miller, JR. and NT. Hobbs. “Recreational trails, human activity, and nest predation in lowland riparian areas.” Landscape and Urban Planning. 2000, Vol. 50, No. 4, pg. 227-236.

- Mortberg, U. and H.G. Wallentinus. “Red-listed forest bird species in an urban environment-assessment of green space corridors.” Landscape and Urban Planning. 2000, Vol. 50, No. 4, pp. 215-226.

- Noss, R.F. “Sustainability and Wilderness.” Conservation Biology. Vol. 5, No. 1, pg. 120-122.

- National Park Service (2002). The Hyde Park Trail, Pamphlet.

- National Park Service (2001). Vanderbilt Mansion: Official Map and Guide, Pamphlet.

- National Park Service (1999). Eleanor Roosevelt, Pamphlet.

- National Park Service & New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (1998).

- National Park Service. www.nps.gov/parks.html. Assessed April 15, 2003.

- Cultural Landscape Report for the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt

National Historic Site. Scenic Hudson & National Park Service (1989).

Building Greenways on the Hudson River Valley: A Guide for Action.

- Orr, D.W. “The limits of nature and the educational nature of limits.” Conservation Biology. 1998, Vol. 12, No. 4, pg. 746-748.

- West and Brechin. Resident Peoples and National Parks. University of Arizona Press: Tuscon, 1991.

Figure 1. Land Ownership in Hyde Park

Figure 2: “Voluntary Trail

Agreement for Hyde Park”

(Source: David Hayes, Park Coordinator Roosevelt/Vanderbilt National Historic Site. Interview 3/28/2003)

Voluntary Trail Agreement for Hyde Park

- Use of the trail will solely be foot-based.

- The Hyde Park Trail Committee will take care of the trail’s maintenance.

- The Winnakee Land Trust will handle the easement, which covers liability issues.

Figure 3: The Greenway in the Hyde Park-Poughkeepsie Area

(Source: The Dutchess County Department of Planning. Greenway Connections. Hudson River Valley Greenway: Albany, NY., 2000. www.dutchessny.gov)

Figure 4: Example of Hudson River Valley Greenway in Sign on Route 9D

(Source: www.hvgateway.com/PT27.HTM)

Figure 5: Schematic of the Hudson River Valley Greenway Management

(Source: www.nps.gov/phso/rtca/grnmgmt7.htm)